Fertility

Fertilizer is used worldwide in farming. It’s used to give plants a boost, increasing yield and ultimately farmers’ profits.

We all know plants need nutrients, especially nitrogen and phosphorus. To give crops a boost, they are often put on fields as fertilizer. But we never talk about where the nutrients themselves come from. Phosphorus, for example, is taken from the Earth, and in just 100-250 years, we could be facing a terrible shortage. That is, unless scientists can find ways to recycle it.

We’ve all heard about the magical combination of being in the right place at the right time. Well for fertilizer, it’s more accurate to say it should be in the right place at the right rate. A group of Canadian scientists wanted to find the perfect combination for farmers in their northern prairies.

Crops just can’t do without phosphorus.

Globally, more than 45 million tons of phosphorus fertilizer are expected to be used in 2019. But only a fraction of the added phosphorus will end up being available to crops.

The impact is two-fold: financial and environmental. “Fertilizer costs are significant for farmers in south Florida,” says Tiedeman. “And phosphorus rock, the most widely used source of phosphorus fertilizer, is in low supply across the globe. It is thought that phosphorus rock resources will only be available for the next 50 to 200 years.”

Warren Dick has worked with gypsum for more than two decades. You’d think he’d be an expert on drywall and plastering because both are made from gypsum. But the use of gypsum that Dick studies might be unfamiliar to you: on farmland.

Too much of a good thing can be a bad thing. That’s certainly true for nitrogen fertilizers.

Without enough nitrogen, crops don’t grow well. Yields are reduced significantly.

Applying too much nitrogen fertilizer, on the other hand, can hurt the environment. Nitrogen can enter the watershed, polluting aquatic ecosystems. Microbes can also convert the excess nitrogen into nitrous oxide, a greenhouse gas implicated in climate change.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations estimates that around 45 million tons of phosphorus fertilizers will be used around the world in 2018. Much will be applied to soils that also received phosphorus fertilizers in past years.

According to a new study, much of that could be unnecessary.

Some relationships can be complicated. Take the one between sweet potato crops and soil nitrogen, for example.

Too little nitrogen and sweet potato plants don’t grow well and have low yields. Too much nitrogen, however, boosts the growth of leaves and branches at the expense of storage roots. That also leads to low yields.

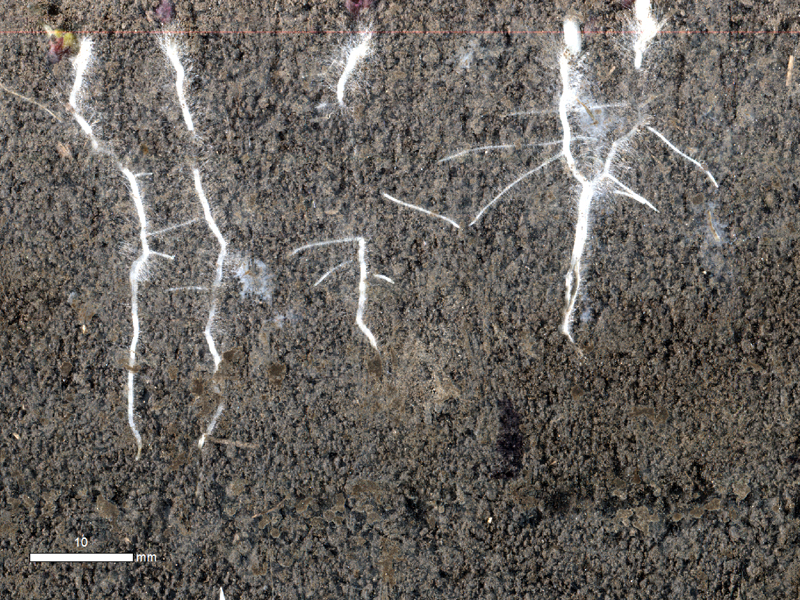

Plants can’t do without phosphorus. But there is often a ‘withdrawal limit’ on how much phosphorus they can get from the soil. That’s because phosphorus in soils is often in forms that plants can’t take up. That affects how healthy and productive the plants can be.