Making wheat and peanuts less allergenic

January 25, 2021 - Adityarup "Rup" Chakravorty

The United States Department of Agriculture identifies a group of “big eight” foods that causes 90% of food allergies. Among these foods are wheat and peanuts.

Sachin Rustgi, a member of the Crop Science Society of America, studies how we can use breeding to develop less allergenic varieties of these foods. Rustgi recently presented his research at the virtual 2020 ASA-CSSA-SSSA Annual Meeting.

Allergic reactions caused by wheat and peanuts can be prevented by avoiding these foods, of course. “While that sounds simple, it is difficult in practice,” says Rustgi.

Avoiding wheat and peanuts means losing out on healthy food options. These two foods are nutritional powerhouses.

Wheat is a great source of energy, fiber, and vitamins. Peanuts provide proteins, good fats, vitamins and minerals.

“People with food allergies can try hard to avoid the foods, but accidental exposure to an allergen is also possible,” says Rustgi. Allergen exposure can lead to hospitalization, especially for people with peanut allergies.

“For others, avoiding wheat and peanuts is not easy due to geographical, cultural, or economic reasons,” explains Rustgi.

Rustgi and his colleagues are using plant breeding and genetic engineering to develop less allergenic varieties of wheat and peanuts. Their goal is to increase food options for people with allergies.

For wheat, researchers focus on a group of proteins, called gluten.

The gluten in bread flour makes dough elastic. Gluten also contributes to the chewy texture of bread.

But gluten can cause an immune reaction for individuals with Celiac disease. In addition, others experience non-celiac gluten sensitivity, leading to a variety of adverse symptoms.

Researchers have been trying to breed varieties of wheat with lower gluten content. The challenge, in part, lies in the complicated nature of gluten genetics. The information needed to make gluten is embedded in the DNA in wheat cells.

But gluten isn’t a single protein – it’s a group of many different proteins. The instructions cells needed to make the individual gluten proteins are contained within different genes.

In wheat, these gluten genes are distributed all over a cell’s DNA. Since so many portions of the DNA play a role in creating gluten, it is difficult for plant breeders to breed wheat varieties with lower gluten levels.

“When we started this research, a major question was whether it would be possible to work on a characteristic controlled by so many genes,” says Rustgi.

For peanuts, the situation is similar. Peanuts contain 16 different proteins recognized as allergens.

“Not all peanut proteins are equally allergenic,” says Rustgi. Four proteins trigger an allergic reaction in more than half of peanut sensitive individuals.

Like the gluten genes in wheat, the peanut allergen genes are spread throughout the peanut DNA.

“Affecting this many targets is not an easy task, even with current technology,” says Rustgi.

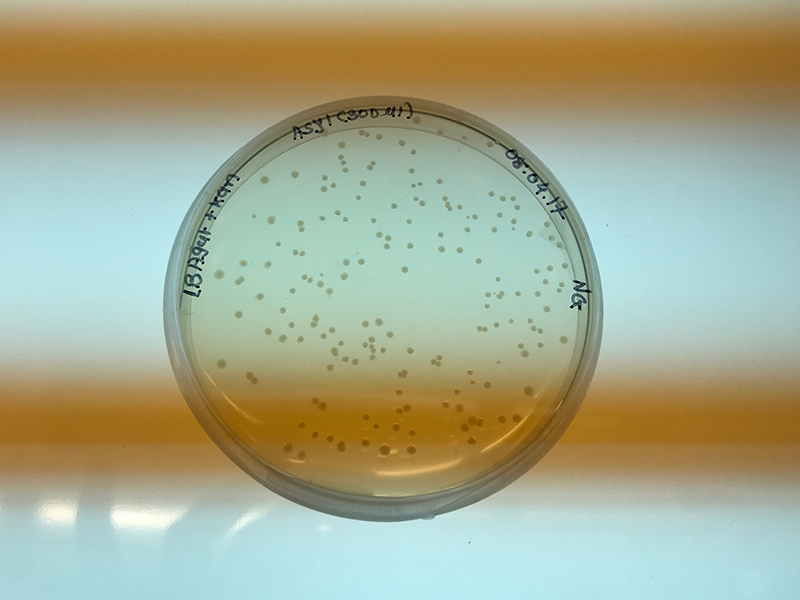

Rustgi and the research team are testing many varieties of wheat and peanuts to find ones that are naturally less allergenic than others.

These low-allergenic varieties can be bred with crop varieties that have desirable traits, such as high yields or pest resistance. The goal is to develop low-allergenic wheat that can be grown commercially.

In addition to traditional breeding efforts, Rustgi is also using genetic engineering to reduce allergenic proteins in wheat and peanuts.

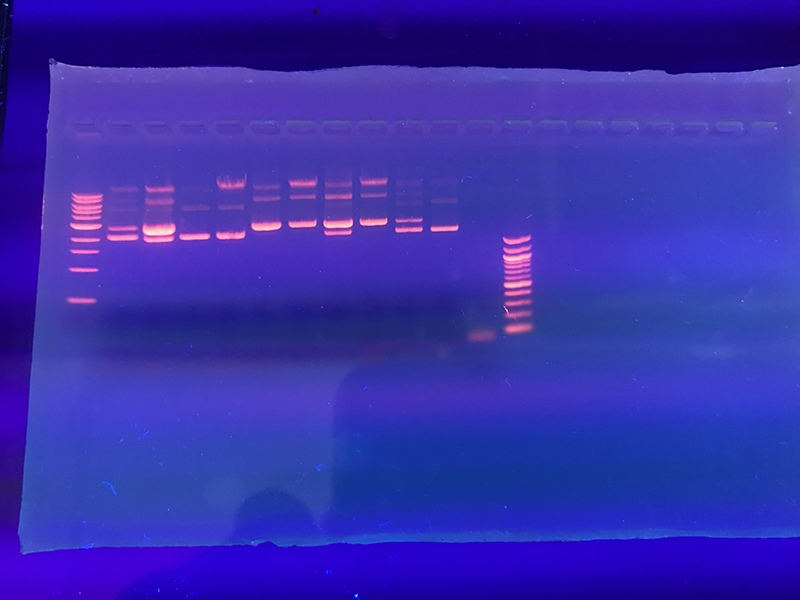

For example, a technology called CRISPR allows scientists to make very precise changes to a cell’s DNA.

Rustgi is using CRISPR to target gluten genes in wheat. Recent improvements in CRISPR technology allow researchers to target many genes at once.

Genes targeted by CRISPR are changed or mutated. This means that cells can no longer ‘read’ these genes to make the specific proteins.

“Disrupting the gluten genes in wheat could yield wheat with significantly lower levels of gluten. A similar approach would work in peanuts,” says Rustgi.

Other approaches include understanding how gluten production is regulated in wheat cells. As it turns out, one protein serves as a ‘master regulator’ for many gluten genes.

That’s important because disrupting this master regulator could lead to reduced amounts of gluten in wheat. Targeting a single gene is much easier than trying to disrupt the several gluten genes.

“Wheat and peanuts are the major sources of proteins to many, especially those living in resource-deprived conditions,” says Rustgi. “Finding affordable ways to make wheat and peanuts available for all is very important.”

Developing wheat and peanuts with reduced allergen levels is a key step toward this goal.

“These crops will also reduce accidental exposure to allergens,” says Rustgi. “Also, they would limit the severity of reactions if exposure did happen.”

Sachin Rustgi is a researcher at Clemson University. This work was supported by South Carolina and National Peanut Boards, Life Sciences Discovery Fund, and Clemson University. The 2020 ASA-CSSA-SSSA Annual Meeting was hosted by the American Society of Agronomy, Crop Science Society of America, and Soil Science Society of America.