Microbes promote lima bean growth

July 19, 2021 - Adityarup "Rup" Chakravorty

Lima beans are packed with nutrients. They are an excellent source of protein and fiber. They are rich in vitamins and minerals.

Lima beans are also good for the environment and farmers. They are effective as cover crops and as green manure.

The benefit of lima beans stretches down even into their roots. There, they house microbes that transfer – or ‘fix’ – atmospheric nitrogen into the soil. Plants can access this fixed nitrogen, which helps them grow.

Researchers in Brazil have identified which microbes work well with lima beans in the drier, northeastern parts of the country. The study was published in Soil Science Society of America Journal.

“We think our findings can be an important component of sustainable agriculture in the region,” says Fatima Maria de Souza Moreira, co-author of the new study.

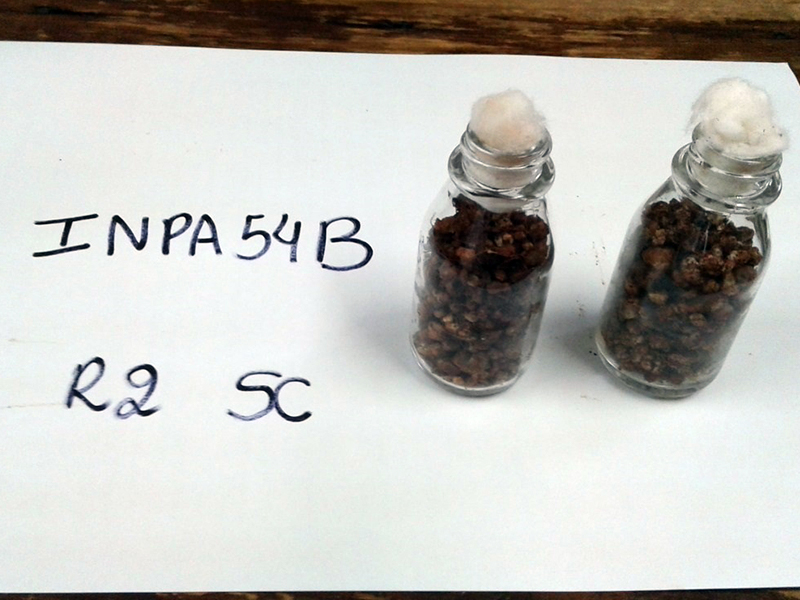

Microbes are often added to seeds or to the soil when preparing for planting bean crops. These additions – called inoculants – can jumpstart the partnership between the plants and microbes.

“Sustainable agriculture management aims to improve natural, helpful processes like nitrogen fixation by microbes,” says Moreira. “Knowing which inoculants work well with lima beans in northeastern Brazil will provide economic and environmental benefits.”

Lima beans – also called butter beans – are an important crop in many parts of the world. Often, these beans are a vital source of food and income in poorer areas.

In Brazil, lima bean is mainly cultivated by small farmers in semi-arid regions.

“Knowing which microbes are naturally present in the root nodules of lima beans in these areas is important,” says Moreira.

“We can then test which species of microbes work best as inoculants to promote lima bean growth,” she says. “Also, we can determine which of these microbes don’t harm animals and humans.”

In addition, climate change makes it even more crucial to get more information about these microbes.

“Knowing more increases our chances of finding microbes that perform well in different soils and different climatic conditions,” says Moreira.

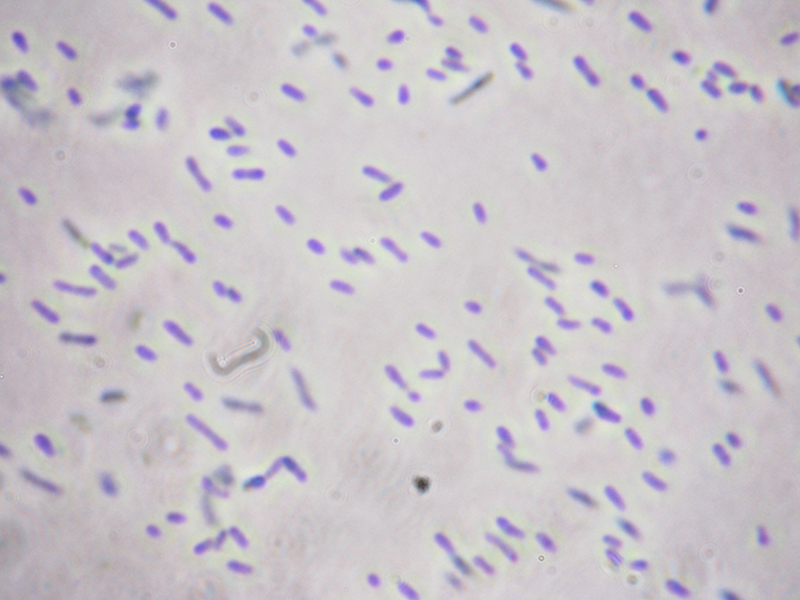

The researchers collected lima bean plants from farms in the northeast Brazilian state of Piauí. They grew microbes isolated from root nodules. Then they extracted DNA from these microbes and analyzed DNA sequences to identify them.

Most of the microbes the researchers identified belong to a group called Bradyrhizobium. These microbes are not harmful to humans or animals and have many advantages.

For example, Bradyrhizobium microbes are genetically stable. That means they tend to not accumulate many mutations in their DNA, and the same strains can be used in agriculture for many years, even decades.

“In fact, Bradyrhizobium strains used in soybean farming in Brazil have been the same since the 1960s,” says Moreira.

Also, the microbes identified in the study were obtained from a semi-arid region with very high temperatures. “They are a great resource for potential use in a warming world,” says Moreira.

The researchers also tested which strains of Bradyrhizobium worked best as inoculants for growing lima beans in the lab. They found several strains that helped lima bean plants grow well under both optimal and adverse soil conditions.

“Microbes are versatile lifeforms,” says Moreira. “Very often they work in different soil types and climate regions.”

But that’s not always the case.

That’s why it’s important to have a large number of microbes with diverse genetic characteristics that can be used as inoculants. That will allow farmers and researchers to choose microbes best adapted to specific soils and conditions.

Researchers are now testing the microbes identified in the study under different field conditions.

“We are also studying them to explore other diverse biotechnological applications,” says Moreira. “For sure, the lima bean/Bradyrhizobium partnership can be an important component of sustainable agroecosystems.”

Fatima Maria de Souza Moreira is a researcher at the Universidade Federal de Lavras in Brazil. This work was supported by CAPES, the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development, and the Minas Gerais Research and Support Foundation.